Ethereal Wreckage

I Listened to the First Four Velvet Underground Albums Consecutively and Here's What I Learned

Listening to the Velvet Underground is not a spectator sport. It’s an initiation, a dive into a soundscape that alternates between ethereal beauty and jagged chaos. It’s not here to make you feel good. It’s here to make you feel everything. This is the sound of a band that could charm angels one moment and set fire to your soul the next. I went album by album - no skipping tracks, no half-measures. Just me, the Velvets, my turntable, and a spiral staircase that descended straight into the heart of human experience. That and several strong drinks. I got to The Velvet Underground because it’s something of a logical step after The Doors. In the arc of what is canonically understood as “classic rock” it makes sense. That said, I didn’t get to the VU until I had a more extensive understanding of pop art, the ‘60s, and Lou Reed’s legacy. What’s more, I didn’t find the album. It revealed itself to me when it determined I was ready. To this day, I’ve heard the Velvets on the radio exactly once, and that was on a rebel-to-the-grain independent radio station in San Diego. Following my experience writing about listening to all six Morrison Doors albums consecutively, it made complete sense to me to listen to the Lou Reed Velvets albums consecutively. I wasn’t ready, but again, that’s not the point. It had to be done.

The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967): Seduction and Destruction

The banana album. That bright, beckoning yellow fruit on the cover promises sweetness, but it's a smirking lie - a cunning little trick. Peel it, and you're not just eating the fruit; you're devouring the forbidden knowledge of a world that isn’t remotely prepared for you, or more likely, a world for which you are not prepared.

Sunday Morning slinks in like a thief in the night, like all proper Sunday mornings do. It’s soft, almost deceptively so - a music box lullaby caught in the web of Lou Reed’s weary croon and a chiming celesta. It’s a promise of safety, of comfort, a whispered assurance that everything might just be okay. It’s also a trap, bait for the uninitiated. By the time you’ve relaxed into its dreamlike haze, the rug’s pulled out from under you with the mechanical chug of I’m Waiting for the Man.

This is a different animal altogether - dirty, jangly, and unapologetically transactional. I’m no longer in a dream; I’m standing on a grimy New York City street corner, watching a transaction of need, desire, and humiliation unfold.

Hey, white boy, what you doin' uptown?

Hey, white boy, you chasin' our women around?

Oh, pardon me, sir, it's furthest from my mind

I'm just lookin' for a dear, dear friend of mine

I'm waiting for my man

There’s no pretense, no glamour - just the unvarnished truth of addiction played out over Sterling Morrison’s insistent guitar and Mo Tucker’s pounding, primal drums.

Two tracks later, I’m blindsided by Femme Fatale. That’s not entirely true, now that I look at what I just wrote. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve listened to this album. Several dozen at least. So I do know what’s coming, but over the last several years I’ve tried to adopt Rick Rubin’s idea of listening with no expectations. Rick’s a Buddhist, so this idea makes complete sense. Forget all the other times you’ve heard a song. Forget, for a moment, that you know when the bass kicks in, or when the drum break comes, or when the bridge hits, or where the guitar lead-in is. Listen as if it’s the first time you’ve heard a thing. Forgo all your previous knowledge, about the band as a whole, about the artists in the band, and about all those things we maniacs obsess over. Listen with no expectations. I made a conscious effort to do that with this odyssey, and it fucking changed everything.

Nico’s icy, otherworldly voice glides over a deceptively tender arrangement, each word a scalpel carving into my understanding of love. It’s heartbreak delivered with surgical precision - beautiful, delicate, and utterly devastating. It’s the soundtrack to every romantic ruin I’ve ever endured, sweetened just enough to make the poison palatable.

Then, Venus in Furs. The entire dynamic shifts, and the thin mask drops. This isn’t just music anymore; it’s full-blown necromancy, a séance for the twisted and the taboo. Reed’s deadpan drone weaves through John Cale’s relentless viola, dragging me deeper into a world of leather, whips, and masochistic ecstasy. It’s hypnotic, relentless, and unforgiving - a manifesto for the unrepentantly depraved. I was very turned on.

By the time I reach Heroin, I’ve been stripped of all illusions. This isn’t a song - it’s a cinematic descent into blissful nihilism. The tempo rises and falls like the ebb and flow of addiction, each crescendo a needle plunge, each lull a momentary reprieve before the chaos resumes. It’s not asking for my sympathy; it’s showing me the unvarnished truth of chasing the void. One does not simple listen to Heroin (Insert Boromir meme here); one lives it, and by the end, I’m left hollowed out and shaking.

All Tomorrow’s Parties keeps the knife twisting. Nico’s voice returns, spectral and detached, a stark counterpoint to the plodding, funereal march of the music. It’s the sound of dreams shattering under the weight of expectation - a dirge for the disillusioned.

The Black Angel’s Death Song and European Son don’t offer a reprieve. If anything, they double down, pushing me further into the album’s chaotic, existential abyss. The former is a whirlwind of cryptic lyrics and dissonant screeches, while the latter closes the album with an explosion of feedback and chaos as if the band is tearing down the very structure they’ve just built.

By the time the needle lifts, I’m not merely a listener, I’m a survivor. The Velvet Underground & Nico is an initiation. It opens with a deceptive lullaby, takes one through heartbreak, perversion, and addiction, and spits one out the other side, battered but transformed. It cuts into the glossy veneer of human existence and leaves the truth writhing on the floor. No hand-holding, no safety nets. Unapologetic exposure to the grotesque beauty of everything we pretend not to see.

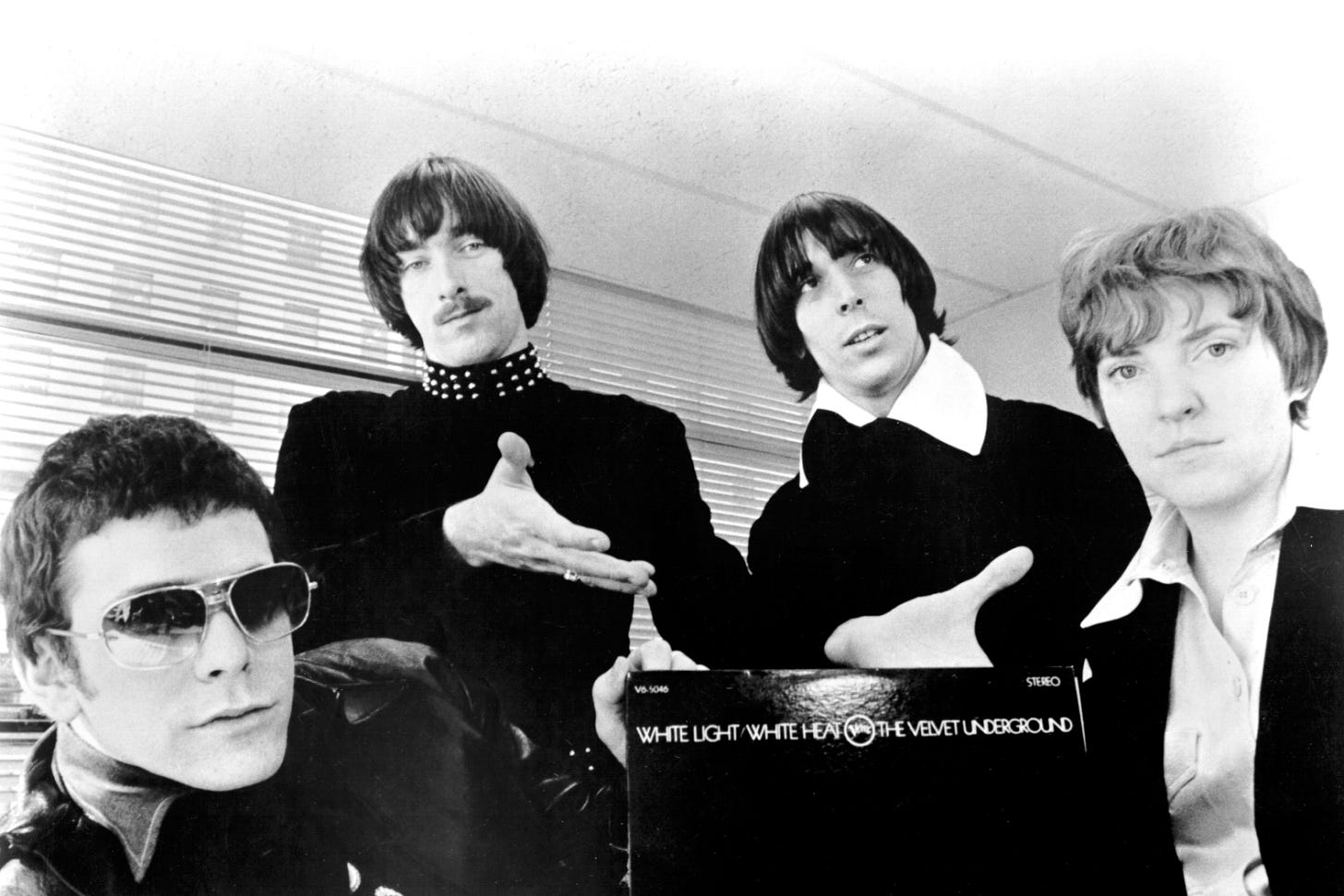

White Light/White Heat (1968): Anarchy in Sound

This isn’t music for the faint-hearted. Fuck, for that matter, it’s not even music for the strong-hearted. White Light/White Heat is a feral, rabid beast, snarling and snapping at anyone foolish enough to come near. It’s not inviting. It doesn’t seduce. It mauls you with sound, dragging you into its anarchic pit of distortion, noise, and venom. Lou Reed and company dropped Nico and Warhol (for the most part), took the rough edges of their debut album, and sharpened them into deadly weapons, amplifying the abrasion until it teeters on the brink of being unlistenable.

The title track kicks things off like a shot of electric adrenaline into the bloodstream. This is Vincent Vega stabbing Mia Wallace in the heart. Reed’s delivery is taut and jittery, riding on a wave of unpolished sound that careens forward without a care for subtlety or finesse. This isn’t a song you relax to; it’s a song you endure. The driving rhythm pounds like a heartbeat in overdrive, a sugar high on the verge of collapse. It doesn’t care if you’re along for the ride because it’s already out the door and halfway to oblivion.

Hmm, hmm, white light

Aw, I surely do love watching that stuff shoot itself in

Hmm, hmm, white light

Watch that side, watch that side

Don't you know it's gonna be dead in the drive?

The Gift is an absurd, macabre masterpiece that could only come from a band with no interest in playing by the rules. It’s also nearly unlistenable. The original recording quality of the album is for shit, and do not offer up some harangue toward me. The recording quality wasn’t some revelatory decision the band made. It was a rush job with new equipment provided by Vox under a new deal the band signed with them. It was all the buzzwords music critics use to make a badly recorded thing seem more interesting than it actually is. Lo-fi, distorted, overdriven, raw… yeah, I got it. It’s The Velvet Underground - one does NOT need to hype bad production as “interesting” for a band that’s already in the top 1% percentile of interesting bands. Most of the band didn’t care for production quality either! The VU doesn’t need you to suck their collective dick, though to be fair, they probably wouldn’t mind, but they wouldn’t respect you either. Those critics are using nonsense as an ex-post facto patch to cover up their initial hatred of the album, and the album deserves to be hated. I also mean that in the best possible way. It would be nice to hear what the fuck is being said, since several hundreds of people went through the trouble of playing it, recording it, pressing it, packaging it, shipping it, and selling it. Seems fair, yeah?

Meanwhile, back at the ranch… John Cale narrates a grim, blackly comedic tale of love, misunderstanding, and gory tragedy, all in his dry Welsh drawl, over a filthy, churning groove. The juxtaposition is grotesque and oddly hilarious, like a car crash in slow motion that I can’t look away from. It’s storytelling at its most deranged, a testament to the Velvet Underground’s refusal to separate art from chaos.

Lady Godiva’s Operation follows, and it’s a surreal patchwork of fragmented vocals and disorienting shifts. It’s dissonant, dreamlike, and deeply unsettling, like drifting in and out of consciousness during a fever dream. The song refuses to make sense, and that’s its power. It left me adrift, searching for meaning where none existed. This was a feeling with which I had to get intimately familiar.

Dressed in silk, Latin lace, and envy

Pride and joy of the latest penny fair

Pretty passing care

Hair today now dipped in the water

Making love to every poor daughter's son

Isn't it fun?

Fun is decidedly not the word I would use.

Here She Comes Now is the closest the album gets to a reprieve, a gentle sigh in a hurricane. But even here, the calm is deceptive. There’s a tension lurking beneath the surface, a sense that the storm hasn’t passed - it’s just waiting for the next strike.

Then the VU serves up I Heard Her Call My Name, and all pretense of restraint is obliterated. Reed’s guitar tears through the mix like a buzzsaw, slicing the track into jagged, bleeding pieces. It’s loud, chaotic, and just fucking brutal, the musical equivalent of a nervous breakdown. Every note screams with intensity, a sonic exorcism that leaves no room for subtlety or mercy and it left me saying to myself “what the shit was I thinking with this exercise?”

Then… finally… Sister Ray. Seventeen minutes. Seventeen minutes of unfiltered mayhem. This is a goddamned endurance test and I’m committed to endure. The relentless, pounding rhythm locked me in, refusing to let go, while the band churned out a maelstrom of sound that ground my brain into a paste. Reed’s fragmented lyrics weave in and out, a blur of debauchery, violence, and nihilism. There’s no structure, no resolution - just a descent into the abyss. Remember, one stares into the abyss and screams into the void. It’s messy, loud, and completely unrelenting, a testament to the Velvet Underground’s willingness to push boundaries until they disintegrate.

What makes White Light/White Heat truly remarkable is its refusal to pander. This album does not care if I like it. It doesn’t care if I understand it. It exists in defiance of convention, a snarling middle finger to the very idea of accessibility. It’s art as confrontation, music as a weapon, chaos as catharsis.

By the time it’s over, I’m not the same. I’ve been left to piece myself back together in the silence that follows. White Light/White Heat isn’t here to be liked. It’s here to wreck us, to challenge everything we thought music could be, and to leave us wondering why we ever tried to tame it in the first place.

The Velvet Underground (1969): Beauty Through Restraint

This is the sound of a band stepping out of the shadows and into the light, not to bask in its warmth, but to show you every scar and bruise they’ve accumulated along the way. It’s not an album that screams for your attention. It whispers, it sighs, it lets you lean in and stumble into its revelations. With Doug Yule stepping in to replace John Cale, the Velvet Underground trades some of their experimental chaos for a quieter kind of subversion. But don’t mistake “quieter” for “weaker.” This album doesn’t pull its punches; it just knows where to aim to hurt the most.

Candy Says opens the record like a diary cracked open to the most vulnerable page. Doug Yule’s fragile, almost hesitant vocals deliver a quiet masterpiece of self-doubt and longing. It’s a tender hymn for anyone who’s ever felt like a stranger in their own skin. The simplicity of its arrangement - a gently strummed guitar, a hushed rhythm - feels like a deliberate stripping away of armor. This isn’t the Velvet Underground inviting me to a party; this is them asking if I can sit with them while they bleed.

What Goes On shifts gears, but not into anything remotely resembling joy. Its hypnotic, driving riff is pure Velvet Underground - relentless, repetitive, and insistent. There’s an urgency beneath its surface, a barely-contained energy that threatens to spill over but never quite does. It’s the sound of a band refusing to let go of their edge, even as they explore softer textures. The interplay of rhythm and melody feels like a heartbeat, pulsing with the tension of a band caught between who they were and who they’re becoming.

And then… Pale Blue Eyes. What can you even say about a song like this? It’s heartbreak distilled into sound, the kind of track that stops you mid-breath and leaves you staring at the ceiling, wondering where all the time went. Lou Reed’s voice carries the weight of a hundred unspoken apologies, a thousand unsent letters, all the hints, lies, allegations, and things left unsaid. The guitar line weaves through it like a faint trail of smoke, something fragile and ephemeral. This is an ache, a confession, a moment of staggering intimacy pressed into vinyl.

Skip a life completely

Stuff it in a cup

She said, "Money is like us in time

It lies but can't stand up

Down for you is up

The album doesn’t shy away from experimentation, though. The Murder Mystery is an exercise in controlled chaos, a fractured, dual-vocal fever dream of overlapping stories and shifting perspectives. It’s dizzying, disorienting, but somehow still inviting. Where their earlier experimental work often felt designed to alienate, this feels like an invitation to dive deeper, to get lost in the labyrinth they’re building. It’s challenging, yes, but not cruel - a strange puzzle that rewards those willing to stick with it.

The band hasn’t completely abandoned their bite. Beginning to See the Light carries a defiant edge, a refusal to sink entirely into introspection. It’s as if they’re reminding me - and themselves - that there’s still fire beneath the surface, even in their quieter moments.

By the time the album closes, I’m left with the sense of having been invited into something deeply personal. The Velvet Underground isn’t a manifesto or a declaration. It’s a conversation, a moment of reflection caught between breaths. This is a band rediscovering themselves in real-time, peeling back layers of noise and distortion to reveal a fragile, beating heart beneath.

It’s not about making a statement; it’s about making a connection. And in doing so, they don’t merely invite me into their world - they remind me of my own. They’ve pulled back the curtain, and what’s behind it isn’t wreckage - it’s life, in all its messy, beautiful, heartbreaking glory.

Loaded (1970): Pop with a Pulse

If Loaded is the Velvet Underground’s attempt at making a “pop” album, then their concept of pop belongs to another universe entirely - one where the radio waves are haunted by poetry, and hooks come with a side of existential dread. This isn’t a sellout; it’s a subversion. They took the scaffolding of mainstream rock and painted it with the dirty hues of their world. It’s their most accessible album, sure, but it’s still unmistakably the Velvet Underground: sincere, swaggering, and razor-sharp.

Who Loves the Sun feels like a wink and a nod to the bright-eyed optimism of ‘60s pop, except Lou Reed drenches it in irony (Because he’s still Lou Reed). The sunny melody clashes with lyrics that sound like they’re being whispered through clenched teeth. It’s a breakup song disguised as a day at the beach, or maybe the other way around - a subversive start to an album that keeps tugging at your expectations like a loose thread.

Who loves the rain?

Who cares that it makes flowers?

Who cares that it makes showers since you broke my heart?

Sweet Jane is the Velvet Underground at their most iconic. The swaggering riff is pure earworm material, strutting forward with effortless cool, while Lou Reed’s half-sung, half-spoken delivery feels like a sly confession to the listener. “And anyone who ever had a heart…” It’s a line that grabs you by the collar and refuses to let go, a reminder that Reed could deliver poetry with the same weight as a punch to the gut. This rapidly makes itself apparent to me that it’s a manifesto for surviving heartbreak with style.

Rock & Roll feels like the spiritual sibling of Sweet Jane. This time, it’s not about romantic longing but salvation. Lou Reed spins a tale of a young girl saved by the transformative power of rock music, turning a personal revelation into a communal hymn. The track builds and builds, each chord strumming a little closer to transcendence. By the time it hits its peak, I’m testifying.

But Loaded isn’t just about swagger; its heart lies in the quieter moments. New Age is a love letter to something that slipped away before it could be grasped. It’s wistful, haunting, and strangely uplifting, like a postcard from a parallel universe where things worked out just a little better. Doug Yule’s vocals lend a soft vulnerability to the track, creating a dreamlike quality that stays with you long after the music fades.

Oh… oh… Oh! Sweet Nuthin’, the sprawling, nine-minute closer that feels like a sermon for the broken, a prayer for the downtrodden, a hymn for those who’ve lost everything and found themselves standing on the edge of nothing. It’s both devastating and cathartic, building slowly until it bursts into a tidal wave of sound and emotion. By the end, I’m left feeling wrecked but strangely whole, as if the band has siphoned all my sadness and turned it into beauty. It also contains one of my very favorite guitar solos in popular music (if one can accurately call this popular music). I know Sterling Morrison’s work here is not technically savvy or deeply profound, and you cannot imagine the enormity of the shit I don’t give. It feels perfect to me. In a catalog filled with deeply unsettling feelings and moments, the solo here feels, bizarrely, holy.

This record feels like the culmination of everything the Velvet Underground ever was. It’s a reflection of their evolution as a band: the experimentation of White Light/White Heat, the introspective beauty of The Velvet Underground, and the jagged edges of their debut. Instead of looking backward, Loaded looks forward.

Not for Everyone - Thank Whatever Gods May Be for That

I’m a card-carrying member of Bombastic Literary Observers Writing Hyperbolic Analyses of Resonant Discs (BLOWHARD), music department, so I’m contractually obligated to tell you the Velvet Underground directly inspired thousands of musicians who are now household names. Apparently, I get a bonus if there’s alliteration, so, to that end, the VU was a resounding influence on Cave, Cohen, and The Cure, Stooges, the Strokes, and Sonic Youth, as well as the Jesus and Mary Chain, Joy Division, and Johnathan Richman. Count Eno, Echo, and Electrelane on the list too. *Checks with HQ…* Okay, good, bonus secured. I did good by BLOWHARD standards. The list of those they influenced is long, it’s really fucking long.

Comparing the catalogs of the Velvet Underground and the Doors feels like comparing two entirely different universes. The Doors invite you into a surreal carnival, complete with dark poetry, Dionysian hedonism, and a strange, hypnotic allure. Jim Morrison’s voice is the guiding hand through a world where sensuality and death waltz together, and the band’s polished production often feels like a lush mirage shimmering in the desert of rock 'n' roll.

The Velvet Underground, on the other hand, don’t guide you anywhere. They throw you into the East River and watch you sink or swim. There’s no polish, no hand-holding, and certainly no mirage. Lou Reed and company give you their fierce reality, often ugly and uncomfortable but always unflinchingly honest. While the Doors flirt with danger and mystery, the Velvets invite you into its heart.

Listening to the Doors is an escapade - a journey through psychedelic landscapes and the shadowy recesses of the mind. Listening to the Velvet Underground is an initiation, a trial by fire that forces you to confront the parts of yourself you’d rather leave in the dark. Both catalogs are transformative, but where the Doors provide a mythic, almost cinematic escape, the Velvets offer no such refuge. Instead, they strip away illusions until only the unvarnished truth remains.

The Doors might leave you with a head full of dreams, but the Velvet Underground will leave you with scars - and you’ll be thankful for every single one. The Velvet Underground were deliberately difficult, abrasive, and at times incomprehensible - but that’s the point.

Their music isn’t for everyone, and it never pretended to be. It’s for the ones who need to feel something, even if it hurts.

And in that, they’re not just a band. They’re a revelation.