Break On Through to What, Exactly?

I Listened to All Six Doors Albums Consecutively and Here's What I Learned

Listening to The Doors’ six studio albums consecutively is like taking a road trip where the car breaks down, you hitch a ride with a stranger, and then, somewhere along the way, you realize the highway was actually a river the whole time. On several occasions during the odyssey, I considered why I was doing this, and each time I shrugged off the voice telling me how dumb this exercise was. The voice was correct, of course, but that’s not the point. The experience is less about getting somewhere and more about experiencing the vast, unpredictable terrain of their sound - and what it reveals about a band that always felt more like an experiment than a cohesive entity, and consequently what and how I felt about myself as a young man taking this ride for the first time compared to now. This trip was about inhabiting the spaces between the notes, letting myself be dismantled and reassembled by the alchemy of Morrison, Manzarek, Krieger, and Densmore. By the end, I was not sure if I’d survived or if I’d simply become part of the chaos.

The Doors (1967): A Cosmic Invitation

The self-titled debut is meeting the charismatic cult leader before you know it’s a cult. I’ve longed been seduced by Jim Morrison’s magnetic presence, Ray Manzarek’s swirling organ, and the general sense that this band doesn’t play music so much as they conjure it. Break On Through (To the Other Side) is an adrenaline-fueled manifesto, the first song on the first record, and the first single. It tells you upfront what this collective’s goals are. Morrison’s voice is less an instrument and more a weapon here, cutting through the air with a feral urgency.

Soul Kitchen emerges from the beaches of Southern California a piece of era-appropriate pop but yearning for a bus ticket to Chicago to be with Blues purveyors who so captivated Morrison. Twentieth Century Fox is among the purest pop songs the band ever did. Handclaps, a bitchin’ solo, a built-in pun about good-looking chicks, it’s about the most recorded fun the band ever allowed themselves to have.

By the time Light My Fire rolls around, I’m not so much a listener as I am a participant in a ritual. The album is primal and polished, experimental yet controlled a declaration of intent that feels both timeless and unhinged. The album is a paradox. Light My Fire is a perfect example - a pop song masquerading as a jazz odyssey. Krieger’s guitar solo meanders and burns, while Manzarek’s organ feels like it’s channeling some otherworldly force.

A few twists and turns down Late ‘60s Way, and we arrive at The End. This is Morrison at his most unhinged, unraveling a mythic, Oedipal horror over eleven minutes of simmering menace. It’s a ritualistic dissection of the human psyche that left me questioning my place in the universe (and with a strong desire to rewatch Apocalypse Now, but there was no time for that. I had to focus. I was on mission, dammit).

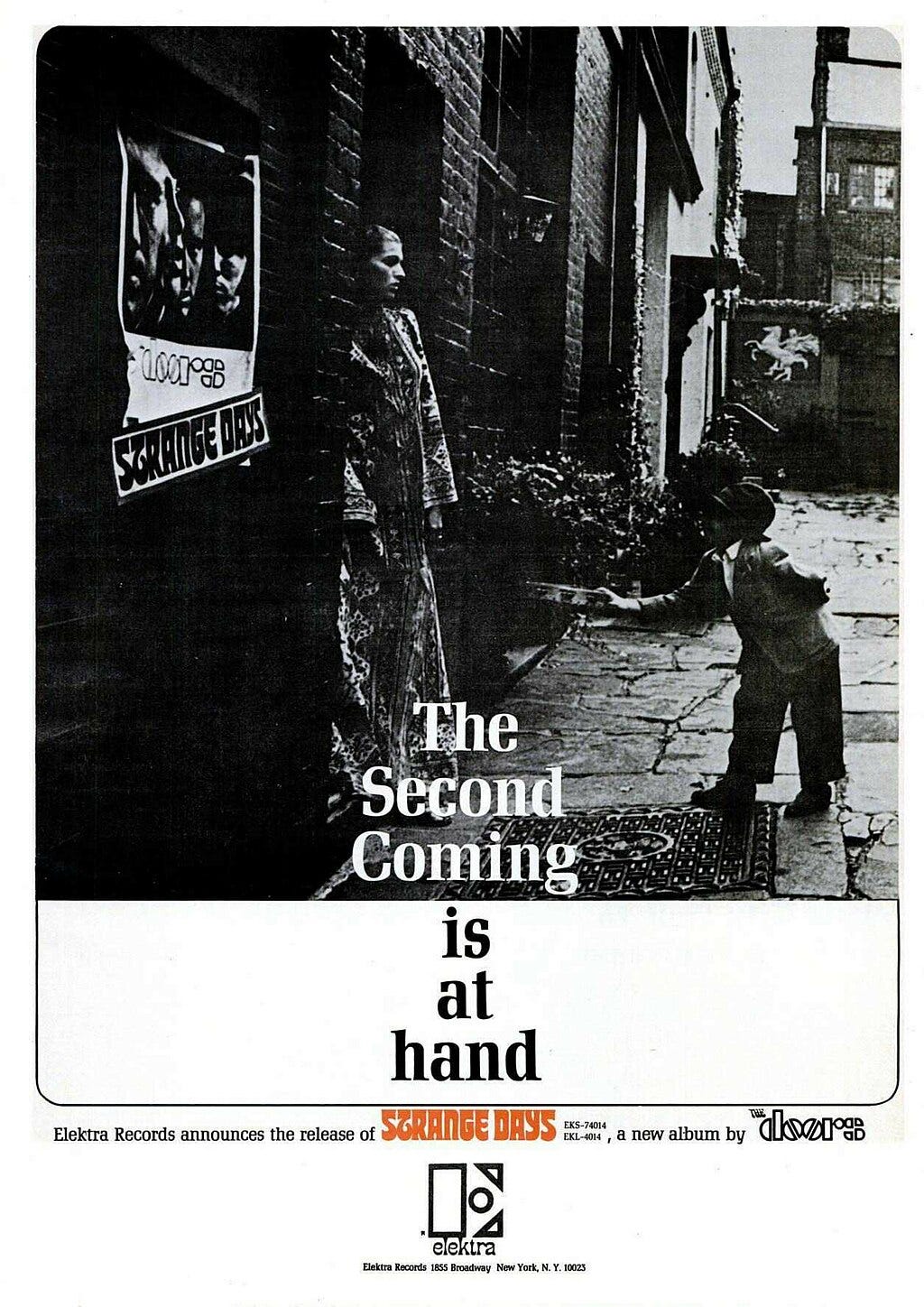

Strange Days (1967): The Weird Gets Wilder

Strange Days doubles down on the psychedelic mysticism and carnival freak-show energy. It’s the band fully embracing their weirdness as if they’re saying, Yeah, we’re strange - let’s do some peyote and I’ll show just how strange. Love Me Two Times showcases their knack for mixing existential melancholy with sexual swagger. The album feels less cohesive than their debut but more expansive, a peek into what happens when the leash is loosened.

If the debut album is an invitation to chaos, Strange Days is the chaos itself. The title track feels like the soundtrack to a nightmare you can’t wake up from, Morrison’s voice slithering through the cracks in your mind. The music is tighter, and more deliberate, but it’s also darker, as if the band has realized the power of their own madness.

People Are Strange is deceptively simple, a waltz for the disenchanted, the alienated, the people who don’t belong. Morrison croons with a knowing smirk, his voice both comforting and disconcerting as he delivers one of his better vocal performances - perhaps because he wasn’t trying so hard to be disconcerting and, well… strange. I wrote about it here.

Horse Latitudes… let me gather my thoughts on this fucking… thing. To begin, (and this is the well-studied sailor in me talking) the Horse Latitudes exist in the subtropics between 30 and 35 degrees. The wind very nearly dies in this area, and sailing ships were known to jettison cargo to make their vessels lighter. This meant ships would send living animals into the drink. I’ll let you piece together the rest. What Morrison’s poetry (and behavior) has taught me over the years is that he was unafraid to venture out to the far-reaching and fragile limbs, both literally and figuratively. Horse Latitudes holds little, if any, value for me, but it IS a fine example of taking artistic chances however discombobulated.

Awkward instant

And the first animal is jettisoned

Legs furiously pumping

Their stiff green gallop

And heads bob up

Poise

Delicate

Pause

Consent

In mute nostril agony

Carefully refined

And sealed over

Moonlight Drive has the distinction amongst the most fervent Morrison fans as being the first song the guy wrote. If I’m being honest, as first songs go, this is fucking superb. Significantly better than my first effort. From time to time, Morrison lets go of the macabre and the theater and embraces the romantic in himself. He fancied himself a bluesman, but he had more Lord Byron in him than John Lee Hooker.

As their debut closed with an 11-minute opus, so does their follow-up. When the Music’s Over features Morrison at his brooding best and the band comes in ferocious. Bluesy Flamenco guitar licks, jazz fills, haunted carnival organ, every member of the band gets theirs, and they’ve become tighter, more seasoned professionals in the ten months since their initial offering. It’s an epic that refuses to be tamed. Morrison’s screams, the crashing instruments, and the eerie silence between verses all build into a storm of existential dread. It’s the sound of a man tearing at the fabric of reality, trying to find something, anything, to hold onto.

Waiting for the Sun (1968): A Flash of Light

Waiting for the Sun is The Doors attempting to reinvent themselves - or at least hinting that they might want to, like a guy who attends exactly two therapy sessions. There’s a sense that the band is trying to rein themselves in, to channel their energy into something more palatable. That said, even their attempts at restraint are tinged with menace. It’s softer in some places, dreamier in others, but still unmistakably them.

That said, the album’s opening cut, Hello, I Love You, plays like a parody of pop music that somehow became a hit - a love letter written in blood, pop with teeth. It’s not whimsical, it’s obsessive. This is the part where I gently remind all my fellow Morrison fans ‘twas Robby Kreiger who wrote all of The Doors’ biggest hits, and he somehow gets overlooked when conversations about interesting guitarists from that era arise.

Quick aside:

Greatest Of All Time conversations annoy me. The greatest guitar player of all time is just as likely to be a widowed woman in Finland as it is to be anyone you’ve heard of, and that includes all the knighted and anointed legends with whom we’re familiar. Interesting guitarists is a much more fruitful conversation - one in which participants are wildly more likely to hear provocative names, names that aren’t so familiar, and are more likely to send friends down exciting rabbit holes. What’s more interesting: listening to the same Zeppelin/Stones/Hendrix/Van Halen tracks or discovering Yvette Young, Omar Rodriguez-López, Al Di Meola, or Marnie Stern?

Regularly-scheduled programming:

This is an album searching for clarity, a reflection of a band both eager to evolve and terrified of losing their essence. Hello, I Love You opens, and then in an exercise of juxtaposition, the Morrison penned Love Street follows, and what becomes apparent is that Kreiger is the better straight-ahead pop songwriter.

And that brings us to the moment the album sheds its pretense of normalcy. Not to Touch the Earth is a fragment, probably the best, of the aborted and near-mythological Celebration of the Lizard. The song is a feverish, hallucinatory sprint through a landscape of surreal imagery and cryptic proclamations.

Dead president's corpse in the driver's car

The engine runs on glue and tar

Come on along, not going very far

To the East to meet the Czar

Morrison is not the prototypical frontman. That benchmark was set by the peacocking Sir Michael Philip Jagger half a decade prior. Morrison is a different entity, fueled less by the Blues (despite his best intentions) and more by lysergic influence and shamanistic idealizations. He didn’t want to play the Blues as much as he wanted to hold a seance with syncopation.

The Unknown Soldier is definitely the band’s most overtly political statement to this point (My memory of the deep catalog doesn’t recall but we’ll see). Morrison’s father, George, was a one-star admiral operating in the Western Pacific against North Vietnamese forces at the time of The Doors’ recording of this album. Given the Oedipal mayhem of The End from the debut, one doesn’t need Freudian analysis to gather there might me a connection. There’s a military march to the gallows and an execution in the song, but it’s superbly well… executed. Well done, is what I meant to say. Obviously.

The real gem, though, is Five to One. It’s a call to arms for the disillusioned and the desperate. Morrison’s voice drips with venom as he declares, “They got the guns, but we got the numbers.” It’s a declaration of war against complacency and conformity, and it’s eerily prescient.

The Soft Parade (1969): The Left Turn

The Soft Parade is the moment the car breaks down. The orchestration is lush, almost suffocating, as if the band is trying to drown their demons in strings and brass. It feels both ambitious and desperate, a Hail Mary pass from a band that’s starting to unravel. Brass sections and orchestral flourishes fight for dominance over the band’s signature sound, and it’s not always a fair fight.

Something is haunting about Shaman’s Blues, like listening to Morrison fight with himself. In some ways, it’s the Fight Club Narrator fighting Tyler Durden, and I’m still unsure who wins. It is as perfect an example of Morrison’s competing influences and aspirations as can be articulated within The Doors catalog, and perhaps predictably, it fails. The band is at its best when one concept heavily outweighs another, and Shaman’s Blues, down to its very name, attempts to strike an equitable balance and suffers because of it.

Producer Paul Rothschild was addicted to cocaine at the time of the recording sessions and battled ceaselessly with Morrison. A cocaine abuser and an alcoholic engaged in a fight for control? Sounds like a fucking nightmare. Couple that with the fact the band went into the studio without any album-ready material created an untenable situation and that situation revealed itself in the form of an art rock, jazz-inspired, psychedelic Blues bouillabaisse that simply cannot or would not coalesce into a fully-realized album.

The title track, The Soft Parade, is as bizarre as anything The Doors ever concocted. It’s sermonistic anger, which dissolves into 18th-century British fair music. Then it swerves again into embarrassingly terrible would-be funk as if the band’s tarot cards predicted the worst elements of the disco era. It shifts again into a sort of Merseybeat playfulness while the man on the mic is singing about catacombs and a monk buying lunch. All of this in the first three minutes. Then, John Densmore puts on his cape in a Herculean effort to save this composition. His rhythm machine starts propelling this vehicle toward a goal he cannot fully realize or envision clearly as the lyrics are hopelessly, needlessly tiresome. Manzarek and Kreiger get in the fight as well, but it’s Densmore’s rescue attempt that nearly pulls off the miracle. It is like watching a running back rush for 200 yards in a losing effort. As Morrison howls nonsense about how it’s getting harder to describe sailors to the underfed, the players are growing tighter as an outfit. This album fails spectacularly, and it fully deserved to fail, but the adventurous musicianship would ultimately play out to their benefit.

Morrison Hotel (1970): The Return to Earth

Morrison Hotel is the ride you hitch with a stranger after escaping the wreckage of The Soft Parade. It’s gritty and grounded. Less an opening track and more of a few shots of 95-proof brown liquor, Roadhouse Blues shelves the medicine man aesthetic from Shaman’s Blues and gives us an original 12-bar blues basher that the band always had in them. The wonderful Lonnie Mack joined the session on bass which fills out the sound, making it beefy, more muscular which is altogether fitting for a song called Roadhouse Blues. Don’t get me wrong, The Doors are still gonna Doors this track up as Jim launches into his version of jazz vocal improvisation, but it bizarrely works.

Peace Frog is the moment in which The Doors become a completely different band than the one most people think they know. It’s funky, it’s paranoid, it’s full of blood and groove and sun-baked dread. It sounds like what would happen if a strip club in the Mojave Desert became sentient and started quoting William Blake. And yet, despite all of this, Peace Frog is nowhere to be found on any version of The Doors’ Greatest Hits. Which raises an obvious question with a less obvious answer: what do we actually mean when we say “Greatest Hits” or “Best Of”?

Now, to be clear, “Best Of” and “Greatest Hits” compilations are both marketing sleights-of-hand. They are born from the same cynical calculus used by fast food companies when they invent a “new” dipping sauce. These albums do not count toward the number of releases a band owes the label, because they’re technically not “albums” in the legal sense. They’re more like contractual placebos. If a Greatest Hits album were a person, it would be the kind of guy who shows up to a high school reunion in a rented sports car hoping people still remember he was prom king.

But here’s where things get complicated (and weirdly metaphysical): a “Greatest Hits” album suggests some kind of statistical objectivity. These are the songs that charted. The songs that got played on the radio. It’s essentially Billboard with a better cover. “Best Of,” on the other hand, is pure editorializing. It’s subjective. It implies that someone—usually someone in a conference room—sat down and thought, These are the tracks that really matter, regardless of chart position.

Record labels love to release both, often in the middle of a band’s career, when they can still leverage relevance. This allows for future re-releases with bonus tracks, alternate takes, and extended liner notes written by the same guy who used to manage a Tower Records in Burbank. Eventually, you end up with four or five versions of the same compilation, all of which feel like the musical equivalent of trying to find the best-tasting Diet Coke.

The Doors’ Greatest Hits dropped in 1980, right after Apocalypse Now reintroduced The End to a whole new generation of people who maybe thought Morrison was just a drunk poet who died in Paris. Danny Sugerman released the first biography of The Doors, No One Hear Gets Out Alive in 1980, and then Morrison arrived on the cover of Rolling Stone in ‘81. He’d been dead for a decade (Gosh, Rolling Stone used to be relevant). The comp sold five million copies, which is probably at least four million more than any studio album they released post-Strange Days. Sixteen years later, the label reissued it swapping out Not to Touch the Earth for The End and Love Her Madly. Still no Peace Frog.

This is not just a minor oversight. This is a philosophical betrayal.

Because if Peace Frog isn’t one of the best Doors songs - or at least one of the most interesting - then what are we even doing here? It’s the Rosetta Stone for understanding how weird and versatile they really were. Leaving it off any compilation that attempts to summarize the band is like writing a biography of Hunter S. Thompson and leaving out the part where he bought a peacock farm and ran for sheriff. It’s not just wrong, it’s misleading.

But that’s the thing with legacy bands and the mythology industry around them. The truth is, most Greatest Hits albums aren’t designed to reflect reality. They’re designed to simulate it, and in that simulation, Peace Frog never made the cut. Which is why you can’t trust any record labeled “Greatest Hits” - unless it includes the funked-up, blood-soaked paranoia of Venice Beach’s most dangerous song.

Ship of Fools is a kaleidoscope of time signatures, flipping between jazz, pop, and R&B like a hallucinating sailor with a busted compass. Land Ho is a deranged sea chanty, some madman’s adventure novel set to rock and roll, with Manzarek turning the organ into a demented circus ride. The Spy lurks in the shadows - Krieger’s intro slow and greasy, Morrison crooning like a war-damaged Sinatra over Manzarek’s jazz-tinged electric piano. Queen of the Highway is the Doors in full metamorphosis: all elegance and brutality in equal measure, a space-age jazz-blues hybrid that sounds like it was written in a motel bathroom while the stars fell down outside.

And Maggie McGill - sweet hell, what a finale. Krieger’s dual-slide riffs scrape and claw, Manzarek’s distorted organ pulses like it’s been drugged, and Densmore keeps them tethered while Morrison slinks through the wreckage like a panther in a trench coat, growling into the future. It’s the dark echo of L.A. Woman before that beast was born.

Morrison Hotel isn’t a concept album. It’s a survival record. Blues, R&B, psychedelia, and dirty jazz - all boiled down into something grimy, alive, and undeniable. They dabbled before. Here, they committed the crime.

L.A. Woman (1971): The Final Destination

It was always going to be Los Angeles.

L.A. Woman is an autopsy report written in bourbon and ink, signed in sweat by four men who knew the lights were about to go out. By the time Morrison coughed up his last howl into the microphone at the Workshop, the band had traded Hollywood wizardry for dirty realism, stripping back to raw muscle and black leather blues. They sounded real, for the first time in years. Not cinematic. Not mystical. Just four guys in a grimy office space on Santa Monica, running cables past ashtrays and half-empty bottles, cooking something primal and alive before it all went cold.

And Jesus, did it live. The title track is a monster. Seven minutes of burnt rubber, heat mirages, and freeway ghosts. Krieger starts it with a jagged guitar snarl pretending to be a Dodge Charger in heat, and Manzarek floats in like neon rain. Densmore rides his cymbals like a detective on speed and Jerry Scheff’s bass doesn’t walk - it lurks. Then Morrison kicks in, voice thick and ragged, crooning like a man who’s been sleeping in his boots for a week, howling poetry at the city that made him a king and then tried to bury him in the gutter.

L.A. Woman is a love letter written on bar napkins and police reports. It’s also a breakup note to the city of angels - bloody, beautiful, and forever just out of reach. And in the bridge:

I see your hair is burning

Hills are filled with fire

He becomes the city. Or maybe he becomes something else. Mr. Mojo Risin’ - his name, scrambled into a manic incantation. An alter ego or a death sentence. Maybe both.

The rest of the album sways between blues grit and apocalyptic beauty. The WASP (Texas Radio and the Big Beat) is the finest of Morrison’s poetry exercises the band ever executed. His poetry is coherent and present.

Out here on the perimeter, there are no stars

Out here we is stoned, immaculate

And

I'll tell you this, no eternal reward will forgive us now

For wasting the dawn

His poetry workouts are uneven at best, but when they’re good, they still hit like good LSD.

And then - Riders on the Storm.

The Doors never sounded more haunted. A seance with thunder in the distance, electric rain curling behind Morrison’s voice as he whispers his way into eternity. A killer on the road, and you’re stuck in the passenger seat. Manzarek’s Rhodes spills like mercury, Scheff’s bass creeps low like a heartbeat on quaaludes, and Densmore barely taps the cymbals, like he’s afraid of waking something. It’s soft, hypnotic, lethal. A jazz noir lullaby for the damned. And Morrison doesn’t sing - he haunts it. He’s already gone. Just a voice in the static.

People call it uneven. Sure. Life is uneven. So is death. But this wasn’t supposed to be polished. This was a transmission from the edge - recorded fast and without the safety net of polish. This is what happens when you push past the artifice and hit bone.

L.A. Woman was the last thing The Doors did before Morrison disappeared into the Parisian void. It’s not just their most blues-soaked album - it’s their most human. No gods, no ghosts. Just men. Tired, brilliant, unshaven men clinging to the last great groove before the lights went out. And somehow, that makes it the most important record they ever made.

My Trip

It happened in 1991, and I swear something broke in my skull when Oliver Stone jammed his fever-dream vision of The Doors into the bloodstream of American pop culture. He took a dead rock god and resurrected him as a screaming fireball of sex and nihilism - and MTV, the god-machine of pre-adolescent revelation, wrapped it up and hurled it into my face.

I was eleven. Pre-pubescent and synapse-deep in a time when the golden age of hip hop was pounding at the gates and grunge was just starting to leak up through the floorboards like black mold in a church. And then bam here comes Stone’s video for Break on Through, cut from his hallucinogenic freakshow of a biopic: fire, naked bodies, simulated jerking-off in cathedrals, and a band that sounded like every vinyl echo I’d heard leaking from my parent’s stereo. Except now it mattered. Now it hurt. Like waking up inside a pagan orgy conducted by whiskey demons and jazz vampires. It was pure transmission. Ritual. Revelation.

And I don’t do casual interest. When something grabs me, I go full fucking spelunker. I hit the bottom of the well and start digging. The Doors became the first band whose full catalog I owned - CDs lined up like sacred texts. I read the poems. The biographies. Watched the film every single day for an entire summer like it was gospel. I knew every goddamn word. I ingested them, and they rewired me.

I learned things in that frenzy. For one, had I been in the band, I’d have punched Morrison regularly. He was the sort of man who mistook attention for communion and chaos for meaning. I’d have bonded more with Densmore, Krieger, and Ray - especially Ray, who was some kind of cathedral-dwelling gearhead mystic. Over time, the spell broke. I’ve known too many real-life Morrisons - beautiful arsonists of their own potential, desperately in need of dental work and a good slap. I’m related to one or two of them. I’ve read better poets. Hell, I am a better poet on a bad day and three hours of sleep. And I no longer have patience for the hagiography that insists every drugged-out howl was some divine communiqué.

But Christ, there was nothing like it. Not then. Not now. The Stooges were rawer. The Velvets more committed. The Flaming Lips more capable of actually pulling off the weird. Pink Floyd was some other breed of headtrip entirely. And sure, if you tossed Tom Waits and The Doors in a blender, you might get something like that mutant Lou Reed/Metallica thing that should’ve been taken out back and euthanized at birth. But The Doors were trying to summon something. Jazz, flamenco, Brecht, Blake, Huxley, Hooker - it was a shotgun marriage of genius and lunacy, and somehow it fucking worked.

What I respect most - what still clings to my ribs like smoke - is that they never once played it safe. They threw the dice every time. Four years. Twelve sides of vinyl. No autopilot. No coasting. They crashed into their own myth like stuntmen with death wishes. And even when they failed, the failure felt worthy. Worth recording. Worth feeling.

So I did it. Sat down and mainlined all six records in one go. By the end, I felt like I’d been chewed up and vomited back through the speakers. Half-blind, half-awake, pulsing with bad chemicals and revelation. It’s not a neat arc, not some tidy hero’s journey. It’s a spiral. A descent. A molotov tossed into the void.

I didn’t listen - I endured. Each record like a fever dream scribbled on motel walls, velvet and ash smeared across every surface. I heard myself in the mess - my capable violence, my longing, my idiot hunger for meaning in a world built from dust and advertising. And I still don’t know how we got from the lysergic hedonism of Break On Through to the cinematic murder-blues of Riders on the Storm in less time than it takes to earn a bachelor’s degree.

The Doors were designed to self-destruct. There was no sequel, no afterlife. Just the crash and the crater. And that’s fine. I’ve walked through the wreckage enough to know that carrying on - really carrying on - matters more than the burnout. But every once in a while, I take a field trip into madness. Just to remember. To remind myself that sometimes you’ve got to crawl out onto a limb just to feel the wind. And when it breaks, you learn if you can fly - or just how hard you hit the ground.

You're very brave. Thanks for tackling this. As a consummate Doors fan, I enjoyed the read. My fave part was if you were in the band, you'd have to punch him in the face. No kidding.

Re greatest hits. . .didn't you ever see the Kids in the Hall sketch about how greatest hits are for housewives and little girls?

https://youtu.be/5xillqqt0Y0?feature=shared