The Fictional Rock and Roll Where Are They Now

For Jane

The dust settles thinly over the streets of Silver Lake, as if untouched by time yet heavy with history. The city is still here, grown wider and sharper, its edges blunted now only by nostalgia. And Jane is here too, but she is not the same.

Jane Bainter is fifty-six years old. She has laugh lines around her eyes, scars on her arms and calves, and a certain kind of light in her. It’s the sort that flickers more than it glows, but she’s always there, steady, a kind of lighthouse for those who can’t quite see through their own fog. She’s thinner than she was, and her hair is short now, streaked with salt and wisdom. It’s almost strange, seeing her in broad daylight, because Jane, for years, belonged to the night.

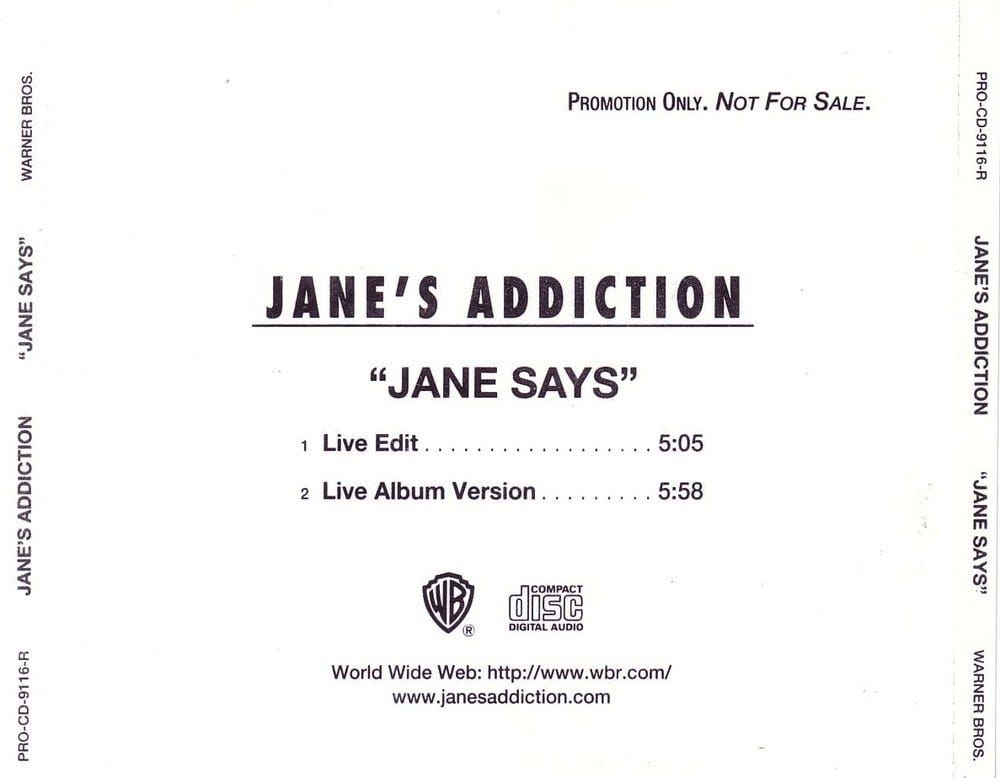

In 1988, Jane Says gave us all a piece of her life, preserved like a butterfly pinned to glass. Her voice rang out not in notes but in stories whispered by someone else, someone singing from the hollow in his chest, his voice heavy with empathy. “She’s going away to Spain, but she doesn’t know the way”, he sang, and in that line was everything about the kind of American girl Jane was. She lived a life pressed up against the boundaries of reason and survival, held in place by the grittiness of her own existence, walking barefoot along city sidewalks, toying with the ideas of escape like some might toy with a prayer they don’t believe in.

Years later, the things Jane chased finally caught up with her. She went to Spain, finally, after years of searching, but only briefly, and it didn’t bring the freedom she thought it might. When she came back to Los Angeles, she was done running. “I’d been running my whole life,” she told me once, on a drizzly November afternoon. “I thought Spain was where the peace was. But it’s not a place. It’s here” - she pressed a hand to her chest, over her heart, the skin translucent and soft from years of rough use and harder love.

Jane found sobriety almost by accident. She'd gone to another meeting with the kind of indifference you expect from someone who’s been thrown from every apartment, every friend’s couch, every narrow strip of hope. But she stayed. And once she was sober, she stayed for others. She has this way about her, a calm that’s equal parts hard-won and heart-wrenching, the kind that doesn’t just draw people in; it holds them together.

In her fifties, Jane became the unexpected advocate for those living a life like the one she left behind. She took the pain of those years and gave it back to the streets, only this time in a language of compassion. Jane volunteers with halfway houses across the city, sometimes staying through the night if someone’s slipping, her presence a quiet proof that survival is more than just waking up another day. She speaks at schools, telling kids the kinds of stories their parents never wanted them to hear but that they need to know. She remembers names, follows up, goes to court hearings, gets up at dawn to drive a friend or a stranger to the clinic.

There’s a kind of sanctity to Jane’s new world, a deliberate, soft-spoken holiness that doesn’t look like much from the outside. But it’s there. I watched her lean across a plastic cafeteria table, taking the hand of a girl barely out of her teens, and in that moment, there was a wholeness to Jane I’d never seen before. “It’s okay,” she whispered, her hand a fragile bridge of strength. “It’s okay.”

She doesn’t talk much about the past. I ask her once if she remembers what Perry Farrell said about her in an interview, how she was the one person he knew who would stand barefoot in a gas station with a fistful of crumpled dollars, eyes lost somewhere he couldn’t reach. Jane laughs softly, her eyes downcast. “I guess that was true. But that was then. I’m here now.” And that’s all she says.

Jane, once the fragile muse of a thousand whispered ballads, now stands as a beacon of resilience. She's long since left behind the chaos of Sergio and his empty promises, those nights of heated arguments and lukewarm dreams. Their relationship, a tempest of longing and disillusionment, remains a ghost in the annals of rock history. Jane doesn’t dwell on it; instead, she channels those scars into her advocacy for women's shelters, ensuring no one else endures what she did.

beautifully written!